Technology Background

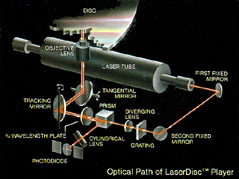

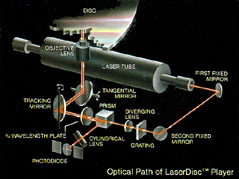

Pioneer Laser-Optical Videodisc Player

The figure on the right diagrams the microscopic detail of the surface of a videodisc. The cylindrical craters you

see drawn following a circular path are, in actuality, minute pits, the information source of the system. On a

typical half hour disc, there may be as many as fourteen billion of these tiny indentations arranged in up to

The figure on the right diagrams the microscopic detail of the surface of a videodisc. The cylindrical craters you

see drawn following a circular path are, in actuality, minute pits, the information source of the system. On a

typical half hour disc, there may be as many as fourteen billion of these tiny indentations arranged in up to

fifty-four thousand circular tracks. A beam of light (see figure on left) focused down to one-thirty thousandth of an

inch passes through a plastic layer, striking the pits which interrupt the reflected beam. This on-off reflected

beam is then translated into electronic impulses.

fifty-four thousand circular tracks. A beam of light (see figure on left) focused down to one-thirty thousandth of an

inch passes through a plastic layer, striking the pits which interrupt the reflected beam. This on-off reflected

beam is then translated into electronic impulses.

Each of the fifty-four thousand circular tracks is equivalent to one television frame, making it possible to have

as many as fifty-four thousand individual pictures on one side of the DiscoVision videodisc. And when the

optical reader head is programmed to play the same track over and over again, a freeze frame results. However,

since there is no physical contact, only a low powered light beam bouncing off the surface, the disc can be held

in a freeze frame mode for as long as you wish without any harm whatsoever to the disc. The one thousandth play

will be just as clean, bright and sharp as the first play.

The optical reader can also move one frame at a time, either forward or reverse. This is called "frame step" or

"Frame by frame display". In addition, slow motion is possible by repeating a series of frames. The rate of

slow motion depends upon how many times you repeat each frame before the optical head moves on to the next one.

By speeding up this process, rapid scanning of the disc, without losing the picture transmission, is also

possible. Finally, each frame of the disc is encoded with a reference number similar to a page number. This is

done at the time the disc is mastered and is the device used in order to take full advantage of one of the

Pioneer videodisc player's most outstanding features, the ability to search out any given frame at any time.

Playing times for laser videodiscs can be extended to one hour per side on both sides of the disc. In this

extended mode, the freeze frame, slow motion, and frame by frame capabilities of the shorter half-hour format are

no longer possible. This is because more than one frame of the source material has been encoded on each

microscopic circular track. However, the laser videodisc's freedom from wear and ability to scan without

picture loss remains unchanged.

The videodisc is manufactured by first producing a glass photo-resist master. Chosen because of its uniformity

and freedom from blemishes, the plate glass is ground and reground with extremely find abrasive to remove all

pits, then optically polished and carefully cleaned. Finally, a thin uniform layer of positive photo-resist is

applied to the glass in preparation for mastering.

The videodisc is manufactured by first producing a glass photo-resist master. Chosen because of its uniformity

and freedom from blemishes, the plate glass is ground and reground with extremely find abrasive to remove all

pits, then optically polished and carefully cleaned. Finally, a thin uniform layer of positive photo-resist is

applied to the glass in preparation for mastering.

Either videotape or film can be used as program source material and all master recording is done in real time.

The image on the left diagrams the process used to record an optical videodisc master. A beam of light from the

laser tube, modulated to carry the source material and critically focused by the optical system, records the

information on the photo-resist coated glass master disc. The sound and picture information are combined in an FM

signal used to modulate a laser beam which alternately blocks or passes the beam focused onto the photo-resist layer

of the rotating master disc. These discrete microscopic areas are exposed at rates of up to ten million per second.

development of this exposed photo-resist layer creates microscopic holes in a spiral pattern known as the track.

(Similar to the pattern diagrammed upper right image). Each revolution of the track is separated by only sixty-five

millionths of an inch. These holds contain all of the information necessary to provide excellent picture

resolution, color, full fidelity sound and synchronization signals.

Once the master photo-resist has been recorded and developed, (see image on right), the recording surface is metalized

with an evaporated metal coating, after which, additional electrochemical processing produces a nickel mother as

well as a sub-master identical to the master. The final tooling, called the stamper, is a mirror image of the

master and is used to manufacture plastic replicas which produce, in every detail, the pattern on the master.

Millions of these replicas can be produced with multiple sub-masters and stampers. Application of a metal

reflective layer and plastic scuff coating results in a finished side which is then bonded to another side to

form the completed videodisc.

Once the master photo-resist has been recorded and developed, (see image on right), the recording surface is metalized

with an evaporated metal coating, after which, additional electrochemical processing produces a nickel mother as

well as a sub-master identical to the master. The final tooling, called the stamper, is a mirror image of the

master and is used to manufacture plastic replicas which produce, in every detail, the pattern on the master.

Millions of these replicas can be produced with multiple sub-masters and stampers. Application of a metal

reflective layer and plastic scuff coating results in a finished side which is then bonded to another side to

form the completed videodisc.

Updated: November 5, 1996

The figure on the right diagrams the microscopic detail of the surface of a videodisc. The cylindrical craters you

see drawn following a circular path are, in actuality, minute pits, the information source of the system. On a

typical half hour disc, there may be as many as fourteen billion of these tiny indentations arranged in up to

The figure on the right diagrams the microscopic detail of the surface of a videodisc. The cylindrical craters you

see drawn following a circular path are, in actuality, minute pits, the information source of the system. On a

typical half hour disc, there may be as many as fourteen billion of these tiny indentations arranged in up to

fifty-four thousand circular tracks. A beam of light (see figure on left) focused down to one-thirty thousandth of an

inch passes through a plastic layer, striking the pits which interrupt the reflected beam. This on-off reflected

beam is then translated into electronic impulses.

fifty-four thousand circular tracks. A beam of light (see figure on left) focused down to one-thirty thousandth of an

inch passes through a plastic layer, striking the pits which interrupt the reflected beam. This on-off reflected

beam is then translated into electronic impulses.

The videodisc is manufactured by first producing a glass photo-resist master. Chosen because of its uniformity

and freedom from blemishes, the plate glass is ground and reground with extremely find abrasive to remove all

pits, then optically polished and carefully cleaned. Finally, a thin uniform layer of positive photo-resist is

applied to the glass in preparation for mastering.

The videodisc is manufactured by first producing a glass photo-resist master. Chosen because of its uniformity

and freedom from blemishes, the plate glass is ground and reground with extremely find abrasive to remove all

pits, then optically polished and carefully cleaned. Finally, a thin uniform layer of positive photo-resist is

applied to the glass in preparation for mastering.

Once the master photo-resist has been recorded and developed, (see image on right), the recording surface is metalized

with an evaporated metal coating, after which, additional electrochemical processing produces a nickel mother as

well as a sub-master identical to the master. The final tooling, called the stamper, is a mirror image of the

master and is used to manufacture plastic replicas which produce, in every detail, the pattern on the master.

Millions of these replicas can be produced with multiple sub-masters and stampers. Application of a metal

reflective layer and plastic scuff coating results in a finished side which is then bonded to another side to

form the completed videodisc.

Once the master photo-resist has been recorded and developed, (see image on right), the recording surface is metalized

with an evaporated metal coating, after which, additional electrochemical processing produces a nickel mother as

well as a sub-master identical to the master. The final tooling, called the stamper, is a mirror image of the

master and is used to manufacture plastic replicas which produce, in every detail, the pattern on the master.

Millions of these replicas can be produced with multiple sub-masters and stampers. Application of a metal

reflective layer and plastic scuff coating results in a finished side which is then bonded to another side to

form the completed videodisc.