The Record That Plays Pictures

by

David Robert Cellitti

This article was originally planned to be a follow up article to World on a Silver Platter

The mid 1970's found the consumer electronics on the threshold of what was eventually to be called

the Video Revolution. Ampex videotape units had been in use for a number of years in professional broadcasting and now

Sony and JVC were perfecting their own versions of the format for home recording. This great leap forward in technology

would allow American's to control when and what they watched in the privacy of their own homes.

So reads the introduction to the worlds first consumer laserdisc catalog handed out to

Magnavision buyers in Atlanta, Georgia on December 14th of 1978.

that appeared in Widescreen Review's Laser Magic 1998.

It has been updated and presented here for the first time by permission of the author.

Still others were fiddling with a concept called Video Disc.

In the fifties, licensing old product for television broadcast had given movie studios a fresh

way to milk cash out of films that were only gathering dust on the shelves. Marketing tests conducted in the early

seventies showed that Americans were interested in building film libraries in much the same way that they had immassed

book and record archives for home use. This meant that video could provide Hollywood with a new level of distribution

for films that had no theatrical re-release potential or for newer product that had lost its muscle at the box office.

In the fifties, licensing old product for television broadcast had given movie studios a fresh

way to milk cash out of films that were only gathering dust on the shelves. Marketing tests conducted in the early

seventies showed that Americans were interested in building film libraries in much the same way that they had immassed

book and record archives for home use. This meant that video could provide Hollywood with a new level of distribution

for films that had no theatrical re-release potential or for newer product that had lost its muscle at the box office.

The DiscoVision videodisc system was the corporate brainchild of MCA president Lew Wasserman.

Its specific origins are covered in my article World On A Silver Platter (Laser Magic

1998) and I won't repeat myself here. For purposes at hand one only needs to know that DiscoVision was MCA's way of

entering the home video market without being beholden or dependent on another company's hardware.

The scope of what DiscoVision was projected to be was truly breathtaking. Whether at home, work or play - DiscoVision would be there. MCA had mom in the kitchen whipping up new dishes via disc, dad learning how to fix the car through specialized training programs and the kids would have a class room away from school via hundreds of cultural and educational albums. Then, at the end of the day the entire family could gather in the rumpus room to watch a movie selected from one of the thousands of movies available from the DiscoVision Feature Film Catalog.

Because standard play discs could capture up to 54,000 single images per side, massive amounts of data could be stored and retrieved easily. Libraries, hospitals, schools and government agencies could all archive millions of documents and distribute the information easily by means of DiscoVision. Television stations would no longer be at the mercy of bulk film prints or magnetic tapes. Shipment and storage of discs was low cost and the random access capabilities of videodisc would allow station engineers to edit and cue programs and commercials with pinpoint accuracy.

From the very beginning, MCA was forever forcing a similarity between a normal 12" LP Record and

their new optical product. Lew Wasserman insisted that his engineers base everything on a 12" platter, not just for

consumer product identification, but also because MCA was already tooled up for replication and packaging of a 12"

platter format through their Decca Records division. It was originally believed that videodiscs would be a relatively

simple item to manufacture and the theory was that, with a little retooling, MCA would be able to have their Decca

division press videodiscs as well. It was also mentioned that MCA planned to release Optically Read Audio Discs that

would "provide up to 15 hours of high quality stereo sound on a single side." Although never explored by MCA at the

time of DiscoVision's initial release, it was a clear precursor to the CD and demonstrates that MCA clearly knew what

the technology was capable of.

Press releases from the 1972 press showings are vague concerning the final form of the MCA

DiscoVision disc. Reflective, transmissive, floppy and rigid discs are all mentioned in the prospectus as being covered

by MCA patents. By the time Kent D. Broadbent, head of the DiscoVision project, gave his paper concerning videodisc at

a 1974 SMPTE Conference, it appeared that consumer discs would be replicated by embossing video information on sheets

of mylar using a web presses. Ease of production was always stressed and the hope was the DiscoVision would be able

to crank out some 2½ million discs annually! (However, Broadbent also tacks on "an alternative process" in which

a stamper is created from which "replicas are thermoformed, typically from polyvinylchloride (PVC), by a method close

to that used to make audio records." Again with the LP's.)

With 90 more lines of resolution than video tape, the option of stereo sound and laserdiscs

available at a fraction of the cost of pre-recorded videotape, DiscoVision seemed to be what Chicago Today called

"the film buff's salvation." One of the main lures of optical disc was the assumed low cost of software. Concerts,

short subjects, television programs and special made-for-disc shows would theoretically be available for purchase at

prices between $1.98 and $9.98 each. Original calculations had discs costing a mere 40 cents per side, "or less than

one cent per minute of playing time for a 60-minute discs (not including the cost of program materials)". By the time

the DiscoVision plant was up and running in Carson, California, MCA and Philips/Magnavox had settled on a rigid, two

sided disc and the cost had risen to $1.25 per side.

sided disc and the cost had risen to $1.25 per side.

This is an historic booklet: never before has such a great number of important, low cost programs been offered for home play.

It is only the beginning. In the months to come, MCA will distribute a steady stream of additional programs in the areas of entertainment and information.

You are a pioneer in a new medium. We thank you for your participation."

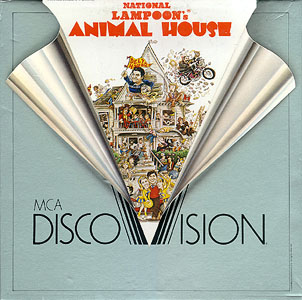

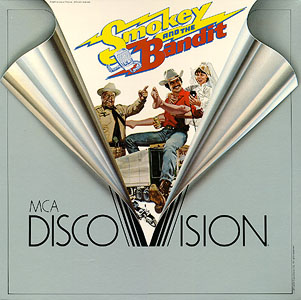

When the first discs and machines first went out the door, top titles like "Jaws" and "Smokey

and the Bandit" were retailing for $15.95, while older titles like "The Sting" and "To Kill a Mockingbird" were to be

had for $9.95. You could learn to cook with Julia Child for as low as $5.95 and The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau

could become part of you home library for as low as $9.95 a show. When one considers a lower quality pre-recorded video

cassette was going for between $50.00 to $100.00 per title, laserdisc seemed like quite a bargain. With prices and

titles like that, who could resist? As one Magnavox ad put it, for the price of a sitter, dinner and admission to

the local cinema, a family could own a movie outright and watch it as many times as they wanted. The Magnavision

sales force was also quick to stress that discs could not be damaged easily and, theoretically, would never wear out

since laserdisc was a non-contact system. It was just a low powered beam of light bouncing off a pit of information

that was then fed into your television set. To hammer home the point of disc indestructibility some over zealous

salespeople would drop a platter to the floor, walk over it, wipe it off and then pop it into a machine for a

flawless play.

and the Bandit" were retailing for $15.95, while older titles like "The Sting" and "To Kill a Mockingbird" were to be

had for $9.95. You could learn to cook with Julia Child for as low as $5.95 and The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau

could become part of you home library for as low as $9.95 a show. When one considers a lower quality pre-recorded video

cassette was going for between $50.00 to $100.00 per title, laserdisc seemed like quite a bargain. With prices and

titles like that, who could resist? As one Magnavox ad put it, for the price of a sitter, dinner and admission to

the local cinema, a family could own a movie outright and watch it as many times as they wanted. The Magnavision

sales force was also quick to stress that discs could not be damaged easily and, theoretically, would never wear out

since laserdisc was a non-contact system. It was just a low powered beam of light bouncing off a pit of information

that was then fed into your television set. To hammer home the point of disc indestructibility some over zealous

salespeople would drop a platter to the floor, walk over it, wipe it off and then pop it into a machine for a

flawless play.

In addition to what was to be had in the Universal library, Paramount, Warner Brothers and

Disney had all agreed to support MCA by opening up their libraries to the new medium. Video tapes could be easily

duplicated by consumers making it difficult for the major studios to control movement of their copyrighted products.

On the other hand, optical disc could not be duplicated easily by consumers and assured studio heads that if a

customer wanted a title they would have to buy it from them. It was MCA's hope that all of the major studios

would see the fiscal advantage of laserdisc and release exclusively on DiscoVision rather than tape. There were some

200 titles listed in the original catalog, a far cry from the thousands of entries envisioned back in 1972.

First time buyers were told that the modest catalog was but a humble beginning and assured - once again - that a

mountain of low-cost software would shortly be theirs.

Sadly, the mountain never arrived.

There are technical glitches to be worked out in any new electronic product, and videodisc

was certainly no exception. Despite the early press that stressed the ease and low cost of replication, the reality

was that defect free optical discs were not easy for MCA to produce. Outside of the 12" size, there was very little

that translated between LP disc and video disc production methods. Given the crude manner in which most DiscoVison

discs were manufactured, it's a wonder that any of it did work or that any of it has survived. Despite the fact

that MCA had been working on its optical disc format for nearly a decade, the actual consumer product turned out

to be a child born in chaos and reared in panic. What constituted clean room status was open for debate in the

beginning. Processes that would eventually be automated by Pioneer in Japan were done by hand in the beginning

at DiscoVision. Contemporary demonstration discs promoting DiscoVision show technicians pulling freshly injected

discs out of presses with suction handles and completed sides sliding off a conveyer belt and bumping into each

other on a holding table. Sides which had been passed by quality control were sprayed with glue and pressed

together by hand in less than pristine conditions leading to inclusions and glue splatters on finished discs.

discs were manufactured, it's a wonder that any of it did work or that any of it has survived. Despite the fact

that MCA had been working on its optical disc format for nearly a decade, the actual consumer product turned out

to be a child born in chaos and reared in panic. What constituted clean room status was open for debate in the

beginning. Processes that would eventually be automated by Pioneer in Japan were done by hand in the beginning

at DiscoVision. Contemporary demonstration discs promoting DiscoVision show technicians pulling freshly injected

discs out of presses with suction handles and completed sides sliding off a conveyer belt and bumping into each

other on a holding table. Sides which had been passed by quality control were sprayed with glue and pressed

together by hand in less than pristine conditions leading to inclusions and glue splatters on finished discs.

The phenomenon commonly referred to as laser rot appeared shortly thereafter. The main culprit appeared to be the glue used to bond the two disc halves together. The reflective coating of the actual disc was sealed with a plastic spray to prevent the surface from oxidizing. For whatever reason (moisture, chemical reactions, heat, etc) the inner protective plastic coating was being eaten away by the glue allowing the metalized surface to be exposed to air infiltrating between the bonded sides thus causing disc failure.

Warpage was another major problem. Early Magnavision machines produced by Philips adhered

to tracking specifications that allowed for very little or no deviations. The original problem of warpage had been

addressed by DiscoVision engineers by the creation of the two sided disc. Once glued together back to back, the

two components stabilized each other. But even with the advent of the two sided disc, there were still warpage

problems and Philips refused to budge on the specs. The problem, they insisted was not their machines, but MCA's

sloppy method of disc production.

Warpage was another major problem. Early Magnavision machines produced by Philips adhered

to tracking specifications that allowed for very little or no deviations. The original problem of warpage had been

addressed by DiscoVision engineers by the creation of the two sided disc. Once glued together back to back, the

two components stabilized each other. But even with the advent of the two sided disc, there were still warpage

problems and Philips refused to budge on the specs. The problem, they insisted was not their machines, but MCA's

sloppy method of disc production.

MCA knew they were in trouble and the great hope was that a 1979 merger with IBM would spell

the end to pesky manufacturing problems. However, when IBM finally assumed control of the Carson plant, they did so

with a "holier than thou" attitude that grated on the MCA workers. Layer upon layer of bureaucracy was ladled onto

what had been a fairly lax environment at DiscoVision and resulted in a combative "Us vs Them" situation at the

DiscoVision labs and pressing plant. At one infamous board meeting, MCA head Lew Wasserman was presented with

glowing statistics about the massive increase of product that had been achieved by IBM since their takeover of

Carson. Tipped off by insiders that defective returns were actually worse under the IBM regime, Wasserman

patiently let the IBM exec prattle on and then interrupted with a question about returns. "Just let me finish,

Mr. Wasserman," was the reply and the executive launched back into his report. "What about defective returns?,"

Wasserman interjected, and again was politely shushed.

The IBM executive droned on as the miffed Wasserman slowly began to remove his wrist watch. Those close to Lew Wasserman knew that the removal of the watch was a signal that the fecal matter was just about to hit the rotating blades. The watch was put to one side as Wasserman slammed his fist onto the board table, the horrendous sound bringing a halt to the representatives presentation. "What about the defective returns!" Wasserman thundered. Shocked by the outburst, the man stopped and began to tap dance around the issue. Wasserman then stopped him and let him know that despite IBM's much touted acumen in the electronics field, he knew they were producing a DiscoVision disc that was no better than what had already coming out of the factory before their arrival and that very little had changed.

Internal hostilities between MCA and IBM only escalated as the future of optical disc continued to look bleaker and bleaker. By 1980 it was estimated that roughly one million videocassette players had been sold to consumers while only a few thousand disc players had made their way into American homes. The moral level among DiscoVision employees continued to deteriorate and an attitude developed among workers that bordered on internal sabotage. If clean room readings didn't come up to spec, it was not uncommon for workers to fudge the figures or even alter measuring devices. Former DiscoVision employee's told me of negligent employee's who would eat their lunch in clean room stations and gleefully pop empty potato chip bags, sending food particles into the air, just for the fun of it. When engineers with DiscoVision Associates were shown the great lengths to which Pioneer Japan was going to maintain a truly clean room status every step of the way, their efforts were met with hoots and catcalls. The American's thought it was overkill. They quickly shut up when they saw how clean the pressings were when compared with their American counterparts.

Theoretically DiscoVision should have shown an immediate profit on product. On paper an average four sided movie should have cost MCA only $5.00 to produce. However a 90% failure rate soon cut out all hope of profits and in less than a year MCA had jacked up the price of a top feature to $24.95 per set and classic titles up to $15.95 each. A considerable hike that angered consumers, but one still reasonable when compared with pre-recorded videotapes.

MCA was so frantic to keep discs going out the door that back orders and replacement discs ended up being a catch-as-catch-can situation for everyone involved. It doesn't appear that there was ever any predictable manner for consumers to order titles. Most distributors on the front lines were constantly having to deal with angry customers who had little or no software for their very expensive Magnavision machines. People bringing back defective sets had to either go without a replacement, wait for a duplicate to arrive or had to choose another title. Even if the dealer had a replacement copy, the reality was that the new set would most likely have defects - most times, not on the same sides. Worse yet, dealers had to return a complete set to DiscoVison for credit or replacement. A consumer wasn't allowed to cobble together a good set from returned defectives. I interviewed dozens of early disc enthusiasts who talked of bringing back a defective set six or seven times until they found something acceptable. Even then, acceptable usually meant a set that had defects they could live with.

Over the years I have located several caches of factory sealed DiscoVision. It was not uncommon

for me to discover a title completely defective upon opening, very rarely did I find a set completely intact. Amazingly

the cleanest sets are usually discs pressed before IBM entered the picture. The average failure rate would appear to be

two to three defective sides per five sided movie, a figure borne out by both consumers and salespeople I interviewed.

Several consumers I talked to spoke of begrudgingly purchasing two copies of a title in order to obtain a good one,

while others spoke of the frustration of returning a defective, highly desirable title and waiting for a replacement

copy that never arrived. Court Attinger, then a buyer for the Bon Marché stores in Seattle, Washington, spoke to

me of spending an entire afternoon in the store going through newly arrived copies of "Thoroughly Modern Millie"

trying to find a playable side four. He opened and tested eight of them before he found one.

the cleanest sets are usually discs pressed before IBM entered the picture. The average failure rate would appear to be

two to three defective sides per five sided movie, a figure borne out by both consumers and salespeople I interviewed.

Several consumers I talked to spoke of begrudgingly purchasing two copies of a title in order to obtain a good one,

while others spoke of the frustration of returning a defective, highly desirable title and waiting for a replacement

copy that never arrived. Court Attinger, then a buyer for the Bon Marché stores in Seattle, Washington, spoke to

me of spending an entire afternoon in the store going through newly arrived copies of "Thoroughly Modern Millie"

trying to find a playable side four. He opened and tested eight of them before he found one.

The beautiful 1978 DiscoVision catalog warns consumers that "Not all programs listed…will

be available at the time of initial distribution." It does, however, assure the buyer that those not available

"will be released early in 1979." Thirty two feature films from the original catalog never materialized. Most

were non-Universal titles, but many were important films that had been used to attract buyers to the medium. Fred

Criss, owner of Videoactive in Los Angeles, California and an early disc consumer still talks about sending angry

letters to MCA trying to find out when "The Godfather" and "The Godfather, Part II" would arrive in stores. The

Magnavox demo disc shown in stores to potential customers goes out of its way to point out the availability of

these two Paramount releases, but they never arrived for purchase.

Aware that numerous side changes would only annoy consumers, the original plan by MCA was to press single sided discs that could be stacked like 45rpm records and have them drop onto a turntable for continuous play. In the press kit issued at the 1972 demonstrations, DiscoVision went to great lengths to point out that a deluxe changer/player unit would be available to consumers that would automatically play six single CAV or CLV sides for a maximum of over six hours unattended playing time. The proposed model never got out of the prototype stage.

Failing the autochanger, alternative plan B was to release feature films in the CLV mode. However the unacceptable level of cross talk between adjacent tracks reduced most early pressings to a mass of squiggly bands beating through the picture as the horizontal and vertical syncs went out of phase. Given that the whole point of optical disc was the superior picture quality, MCA and Phillips had no other choice but to issue the bulk of the original DiscoVision catalog in the more side intensive CAV mode.

The eventual compromise for the CLV mode was the CAA (Constant Angular Acceleration) in

which the deceleration of the disc is accomplished thorough a series of stepped changes in velocity. This cut down

on the problem of cross talk considerably, making Extended Play discs the rule, rather than the exception. In point

of fact, by 1983 CAA became the standard format and the term CLV applied equally to both formats out of habit.

To this day the finger pointing continues between the original members of the MCA and Phillips

camps. Former DiscoVision engineers still claim that it was Phillip's insistence on a rigid rather than floppy disc

that caused much of the problems. The Phillips camp points to the inability of MCA to produce a stable, flat disc

within the agreed upon specifications. MCA claims that the tolerances on the original Magnavision players were

unrealistic, Phillips claims they were betrayed by MCA's refusal or inability to keep to the agreed upon standard.

Inclusions (dirt trapped in the bonding layer or under the metalization) were also a big problem with many of the early DiscoVision pressings. Most of these inclusions couldn't be handled by the Magnavision players and would cause the players to skip or lock. Finally, MCA announced to Phillips that they had solved the problem. They presented to the Magnavox engineers not a method for MCA to produce cleaner more stable pressings, but schematics for servo's that would better tolerate dirty, warped pressings. By this point it was becoming clear to Phillips that MCA was incapable of solving their disc problems through manufacturing.

All this constant bickering is exemplified best by what one former Magnavox employee called The "Looking for Mr. Goodbar" fiasco.

All this constant bickering is exemplified best by what one former Magnavox employee called The "Looking for Mr. Goodbar" fiasco.

Although CAV discs were designed to hold a maximum of 30 minutes of information (or 54,000 single frames), the truth was that most DiscoVision discs started to fall out of specifications or would warp somewhere around the 35,000 to 40,000 frame mark. "Looking for Mr. Goodbar" runs some 136 minutes and should have probably been spread to six sides in order to account for inherent manufacturing problems. For whatever reason, DiscoVision crammed the movie onto five long sides making for discs that refused to play all the way through on the original Magnavision players.

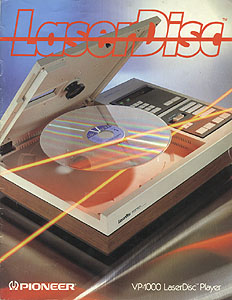

Unhappy customers returning with what they assumed were defective sets were shown that the

discs tracked fine on a brand new Pioneer VP-1000 - a machine that had incorporated the MCA servo specs. The problem,

they were informed by the salespeople was not with the disc, but with their Magnavision machines. It was from

this point that many consumers began to return or trade in their Magnavox machines for new ones manufactured by Pioneer.

As far as the sales force at NAP Magnavox was concerned this was the last straw and the final stab in the back from MCA.

Anomalies

What About Them Crazy Boxes?

The original packaging for optical discs was bulky and expensive. Presentation boxes were

elaborately fabricated out of Styrofoam sheeting, and covered with paper. Three disc movies came in 12½" x

12½" boxes almost an inch thick, while one and two disc programs came in similar packaging the same height

and length but ¾" thick. All discs were slipped into sleeves made of white felt.

These boxes were easily damaged and the carousel kiosks designed to display product had a nasty habit of leaving large dents in the front of the covers. The cloth sleeves had a propensity to tear with use and some of the felt used left a gummy residue on the disc that often interfered with program playback.

Within a year of the original release of DiscoVision, discs started to leave the factory in conventional cardboard jackets and commercially produced plastic/paper inner sleeves. Throughout the remaining few years of DiscoVision's production, titles were often released in both the original foam boxes as well as the standard, familiar LP type jackets. For years disc collectors pondered the purpose of the foam boxes and felt sleeves. When I interviewed Gary Slaten, one of the original DiscoVision engineers, the explanation was really quite simple.

When the question of shipping and storage of discs was first contemplated, one of the

prime concerns by engineers surrounded the issue of moisture in the air. Paper products tend to "breath", capturing

and expelling any dampness in the atmosphere. In the beginning, engineers were afraid that even minor moisture might

effect optical discs and cause failure. To avoid possible problems it was decided that there would be no direct

contact of disc with paper products, thus the resultant foam and felt packages. Once it became clear that average

atmospheric conditions would not effect discs, the go ahead was given to switch to more conventional, less

expensive covers and sleeves.

MCA was, however, stuck with a rather large supply of the original boxes and it was not uncommon to find a title issued in a variety of packages throughout DiscoVision's existence.

Dead Sides and Missing Titles

The most fun to be had with old DiscoVision revolves around the dead sides of titles. After

Pioneer took over the LaserDisc industry, if a movie required an odd number of sides to complete its task, a generic

blank side is bonded to the corresponding programmed material. In the days of DiscoVision, sides from other movies,

over runs and test pressings were sprayed with a clear, plastic coating and used as blank or dead sides. As one

DiscoVision executive explained, with all those rejects coming out of the plant, they had to find some cost effective

way of using them up.

Early on disc collectors realized that a soft cloth and a little rubbing alcohol was all that was needed in order to remove the plastic coating and make the dead side playable. More times than not the mystery side was simply the side of some other available title or an over-run from the General Motors discs being pressed.

However, as time went on, sides of movies thought never to have been mastered started to show up. Sides for Disney's "Monkey's Uncle" and "Prince and the Pauper" turned up, as well as parts of "Sugarland Express," "Bullitt," and "Anne of the Thousand Days."

Word of the relative ease in making dead sides playable eventually made there way back to the plant, and plans were made to run Dead Sides through an embossing machine that would make them unplayable to consumers. However, the discovery was made late in the game by MCA and the Carson plant was sold to Pioneer before anything could be implemented.

We do know that boxes and labels were designed and printed for the entire original catalog. Many of these showed up at trade fairs and conventions promoting DiscoVision. Some of these dummy boxes eventually found their way into the hands of a few private collectors.

Dead side discoveries and bogus boxes led many early disc collectors to speculate that perhaps that everything in the initial catalog had been mastered but not sent into production. Others spoke of titles shipped out and immediately recalled due to mastering errors. Still others claimed that DiscoVision had sent out promotional copies of titles that never were to see general distribution.

Some runs had higher defect rates than others and, yes, there are some pretty weird things to be found in the masterings. The truth is that every dealer I interviewed denied the existence of advance copies and everyone connected with mastering confirmed that there had never been a formal recall of a title and that any master with a defect that blatant would be pulled long before it was sent into production.

Be that as it may, there are still those collectors out there claiming to have owned or seen copies of titles known never to have been pressed or released. One swears that he held an eight-sided CAV pressing of "The Godfather," another a ten-sided copy of "The Ten Commandments". One particularly whacked out collector in the Midwest claims to have a raft of DiscoVision titles that defy all credibility. Among the more incredulous pieces named are "How To Stop Smoking Marijuana," A German DiscoVision Pal pressing of "The Blues Brothers," the Clint Walker made-for-TV movie "Killdozer" as well as a virtually complete copy of the 1933 screwball comedy "My Man Godfrey" compiled from dead sides!

Over the years I have turned up many unusual items from the days of DiscoVision, and shipping records now show that copies of some documentary titles thought never to have been pressed did leave Carson. However, no dead sides, shipping records or physical discs have ever been produced to substantiate the claims for any of these off-the-wall DiscoVision sightings. Until solid proof is offered, these myths can only serve as tempting bait for the collector who yearns for the only complete set of DiscoVision.

Chapter Stops and Frame Counts

The bulk of the DiscoVision catalog consisted of feature films and documentaries meant to be viewed in a linear manner. Nobody considered making chapter's or stops for key scenes in films, let alone adding on supplementary materials or alternative tracks of commentary or isolated scores. On many DiscoVision sides when you hit Chapter Display on your remote nothing will happen as nothing has been encoded. Other times 00 will come up on discs where there are no chapters to be accessed. The first machines included an archaic form of chapter search. When the chapter number was displayed and the scan functionality activated, the changing of a chapter number would bring the player out of the scan mode.

Occasionally on DiscoVision pressings there will be Phantom Automatic Picture Stops - stops that pop up and halt the disc for no apparent reason. On side 3 of "Bride of Frankenstein" copy after copy will chapter halt on frame 12563, and the entire fifth side of Hitchcock's "Frenzy" has an Auto-Stop on every frame (thus making it completely unplayable on anything other than a Pioneer LD-660 or a Magnavox VP-8000, or first generation Pioneer VP-1000). One can only wonder what was going on in the mastering rooms of DiscoVison for anomalies to be so random and unpredictable.

During the MCA era the frame counter on the mastering lathe could be set on any odd number that

happened to be there and then reset to 00001 either when the DiscoVision logo popped up or the opening film credits

started. Since first generation laserplayers simply spun up to 1800 rpms, locked onto a track and played, this didn't

present any problems. Today's players automatically search for and lock onto either frame 1 or 0 as a beginning point

and skip past any unindexed material. Since there is no frame or time numbers prior to actual programming on today's

mastering's everything goes as it should. But put a DiscoVision pressing into many contemporary players and the

machine is likely to go berserk trying to search out frame 0 or 1 at the start of the disc. The number encoded before

the actual program material begins on a DiscoVision master might be 75,248 or 557. The end result is that a number of

DiscoVison sides will not even engage on anything other then first or second generation machines. This has lead some

collectors and dealers to believe that all DiscoVision discs are encoded differently than contemporary laserdiscs.

Believe me, the specs are the same, they were just mastered in a more haphazard way.

collectors and dealers to believe that all DiscoVision discs are encoded differently than contemporary laserdiscs.

Believe me, the specs are the same, they were just mastered in a more haphazard way.

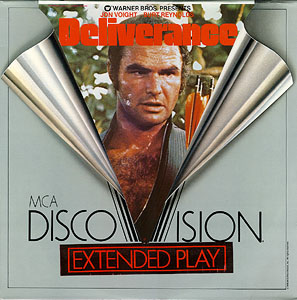

Another oddity concerns frame skipping. The frame count on many DiscoVision discs may jump

anywhere from 20 to 400 or 10,000 frames and possibly even then jump back at some point to the correct number. Not much a problem if your doing linear play, but your machine can get awfully confused if you go looking for as frame that is either missing or out of sequence. Perhaps the most amazing boo-boo of all occurs on the early CLV pressing of "Deliverance" where side three is actually encoded for CAV. Again, if you enjoy watching a laserdisc machine go insane, try hitting any of the special function buttons on your unit while viewing this side and watch the picture go postal.

Laser Lock and Skipping

Laser Lock is a condition where by the image on the screen will suddenly freeze and repeat over and over again like a broken record. This usually happens when the pits of information fall out of the servo's ability to track the pits on the disc correctly. This can be caused by a bad master, but is more times than not is a result of a disc being warped or by inclusions imbedded in the disc surface.

A disc skipping or suddenly speeding up can be caused by a faulty reflective coating, inclusions or - again - disc warpage.

Laser Rot, Drop Outs and other Fun Things

Laser Rot is a term that has been around since the earliest days of laser, refers to a number

of disc aliments. It is a condition that most disc manufactures will tell you doesn't exist.

The most common form of laser rot refers to either video or audio snow that is already present when the disc is purchased or appears on a disc after a period of time. It may start as a few odd speckles here and there and then progress to the point when the disc becomes totally unwatchable. Laser Rot is most commonly the result of the reflective aluminum coating of the disc becoming oxidized. This phenomenon happens when the metalized portion of the disc is either not sealed properly or if the protective plastic coating protecting the disc deteriorates, allowing air to interact with the aluminum surface.

Remember that a laserdisc is actually two single sides bonded together with an adhesive. Many of

the adhesives that DiscoVision used would actually eat through the plastic coatings, while others appear to have failed,

causing sides to delaminate and bow apart, taking reflective coatings with them from adjacent sides.

Because a variety of adhesives were tried with varied results, it was hard for quality control engineers at DiscoVision to pin point problems. Some adhesives appeared stable then would go bad, while other problems occurred when glues were sprayed to heavily or too sparse onto sides.

Drop outs - missing lines of video information - are usually caused by missing pits. This

phenomenon can be caused by either a faulty or worn master, dirt, dust or other contaminants infiltrating the

manufacturing process. Because of the somewhat elastic perimeters for clean room status at the DiscoVision plant, it

is not uncommon to see finger prints, human hair, insect parts or other foreign objects actually imbedded below the

surface of a disc. Freshly pressed sides that passed quality control were checked with a felt pen mark on the back

of the disc before it was sent along to be bonded into a two sided disc. On many early pressings the ink in the pens

used eventually ate through the plastic coating of the back of the disk, showing up as large black V's through the

reflective coating.

A Collectors Guide To DiscoVision

During the early to mid 1980's there was an lively market for clean pressings of DiscoVision titles. This was a transitional time in the laser market when Pioneer was desperately trying to keep the format alive and disc availability was still small compared to what could be had in the tape market. There were only a handful of interactive discs still to be had, mostly educational and information titles. MCA was still recovering from the nightmare of DiscoVision and it would be years before many of the titles from the original catalog would be repressed and put back on the laser market. With CLV the rule of the day in the early 1980's, most of the out-of-print CAV DiscoVision titles were attractive to new disc buyers. A clean copy of a common title like "Jaws 2" went for about $35.00, while a defect free copy of a rare title like "Abbott and Costello meet Frankenstein" could fetch as much as $300.00.

MCA DiscoVision is really the Edison Cylinder of the optical disc format. As such I still find it interesting and search it out. Originally my search was fueled by the desire to acquire CAV pressings of out of print titles. Now it's just a very bad habit.

For those with a collectors mentality and a love of the format, hunting down early optical pressings can be a pleasant pastime while wandering through flea markets and garage sales. These things still turn up, can be had cheaply and the numerous anomalies can provide disc enthusiasts an amusing glimpse into the chaotic world of early disc production.

What's This Stuff Worth?

So you have a tattered CAV DiscoVision copy of "Jesus Christ, Superstar" floating around your

collection. What's it worth? Probably nothing. With the demise of the entire laserdisc industry most used disc stores

are loath to take on any large inventory of used laserdiscs, much less one consisting of DiscoVision pressings. The

defect rates were so notorious that most stores refused to bother with them even when used laserdiscs were a hot

item. Be that as it may, there are still dealers and collectors sitting on large piles of early disc pressings who

honestly believe that they will eventually be able to retire to Florida based on the proceeds gained by selling off

their DiscoVison to hungry collectors. If you ask them for a price you are likely to get a figure between $10.00

and $50.00 per side, no matter what the title.

Today there is a small, but hardy, band of disc aficionados still building libraries of old DiscoVison. Most acquisitions are done through private trading or auctions on the Internet. Fairly common DiscoVision titles turn up on the Ebay Laserdisc site on a regular basis. These items usually fetch anywhere from $5.00 to $20.00 per title, an amazing fact considering that buyers are buying a pig-in-a-poke and generally have no guarantee as to quality.

Some traditionally rare DiscoVision titles have retained their collectability while others

have suddenly become desirable for very unique reasons. Although both "Slap Shot" and "Electric Horseman" have seldom,

if ever, been out of print on laser, the film scores used in their original theatrical releases were retained for the

original DiscoVision pressings. Because of copyright reasons, both features were remastered in later pressings with

new soundtracks. If you want to hear "Electric Horseman" with the original Willie Nelson songs, you have to track

down a good DiscoVision copy. Because both movies were pressed in such great quantities by MCA, the persistent

collector can acquire a clean pressing without a great expenditure of time or expense. Even such common

DiscoVision titles such as "Olivia" have suddenly shot up in price since it has never ever been re-released on disc.

"Olivia" was once a disposable piece of cultural dreck to a disc collector. Now a copy, good or not, can go for anywhere

from $50.00 to $100.00 at auction.

Films that have never been re-released on laser or any other format can also fetch handsome

prices if they are clean copies and you can connect with the right collector. "Fellini's Casanova" and "Diary of

a Mad Housewife" were rare to begin with and neither has ever resurfaced on disc (nor are likely too anytime soon).

But what kind of rabid of collector is going to fork over $300.00 or $400.00 for that all CAV DiscoVision copy of

"Lost Weekend" or "Looking for Mr. Goodbar?" Both titles commanded premium prices during the height of DiscoVision's

collectability back in the mid 1980's. "The Railway Children," a title never re-released on disc and rare even

when DiscoVision was in business recently went on the net for a mere $65.00. Quite a drop from $300.00 it could

fetched in the collector market back in 1985.

The titles which can now command prices in the hundreds of dollars are the handful of

titles from DiscoVision's television catalog. Copies of "The Six Million Dollar Man: Cyborg" and "Six Million

Dollar Man: Secret of Big Foot" both recently went at action for over $250.00 each. Wether this is just a case

of auction fever or a true test as to the discs worth remains to be seen. However, it still shows that, under

the right circumstances, a title can sometimes be worth many multiples of its original retail price.

So You Want To Start Collecting DiscoVision, Do You?

Collectors Mentality is a strange disease. If you suffer from it than you know this from experience. If you don't, no amount of explanation will make it understandable. It's the insane desire to obtain something rare, not generally available to public or impossible to find. DiscoVision is all these things. On that basis alone, looking for old silver boxes with big V-shaped cutouts might appeal to you. There is also a generation coming of age raised on LD's, CD's and CD-ROM's that was still in diapers when MCA and Philips unleashed laserdisc. They are the technocrats financially and emotionally invested in various mediums who want to know more about the origins of contemporary technology. They acquire old hardware and software for their nostalgic value.

Collectors Mentality is a strange disease. If you suffer from it than you know this from experience. If you don't, no amount of explanation will make it understandable. It's the insane desire to obtain something rare, not generally available to public or impossible to find. DiscoVision is all these things. On that basis alone, looking for old silver boxes with big V-shaped cutouts might appeal to you. There is also a generation coming of age raised on LD's, CD's and CD-ROM's that was still in diapers when MCA and Philips unleashed laserdisc. They are the technocrats financially and emotionally invested in various mediums who want to know more about the origins of contemporary technology. They acquire old hardware and software for their nostalgic value.

My advice to anyone wanting to build a library of early discs, whether they are on DiscoVision or just pressings from the early to mid 1980's, is to track down an early hot tube player. The Pioneer LD-660, LD-1100 and Sylvania VP-7200 are all second generation laser players that handle early pressings well and can still be easily located. These babies will give you the best playback and can be picked up for as little as $50.00 used.

For those wanting or needing more information than I have included here, I can do no better

than to refer you to Blaine Young's definitive DiscoVision webpage (http://www.blam1.com/DiscoVision). There you find

an exhaustively researched site containing all the data anyone could possibly require about the subject. His knowledge

on this subject is certainly equal to my own and he is always happy to answer questions.

on this subject is certainly equal to my own and he is always happy to answer questions.

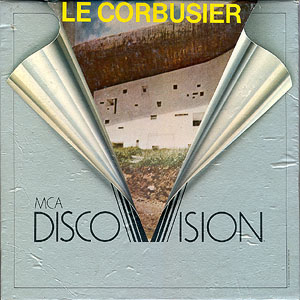

Blaine also has one of the most complete collections from the DiscoVision era of anyone I know.

It includes many, many one of a kind demonstration discs, early single sided test pressings, as well as the only known

copy of "Le Corbusier", a non-feature DiscoVision title everyone believed had never been pressed. He also has sides one

and five from the announced but never released DiscoVision version of "Sweet Charity" as well as side one of a

DiscoVision Richard Pryor concert. Neither of these items are dead side discoveries, but full-blown check discs from

the DiscoVision labs. What makes the Richard Prior disc so mind-boggling is that at no time was it announced in any of

the DiscoVision catalogs! Certainly these are the rarest know DiscoVision pressings ever! Other collectors may make

claims to uniqueness, but Blaine has the goods!